Re-Structuring CLIP’s Language Capabilities

Published:

Authors: Zhiqi Gao

Vision-language models (VLM) like CLIP have transformed how we approach image classification. The performance of these models is heavily influenced by subtle choices such as prompt templates and choice of class names used. Research has shown that prompt templates can sway classification accuracy by as much as 8%, while our experiment shows that the classification accuracy could drop to more than 25% if we replace the class name with their synonyms and 50% if we replace the class name with their hypernyms, both of which highlights CLIP’s sensitivity to linguistic variation.

Over the past decade, natural language processing (NLP) has evolved significantly. Beginning with word2vec in 2013. Word2vec’s word embeddings can capture nuanced lexical relationships through vector arithmetic. The famous equation “king – man + woman ≈ queen.” is a prime example of how word co-occurrences were used to embed semantic meaning. This approach emphasis on maintaining synonym and hypernym relationships stands in contrast to CLIP’s text encoder, which is primarily optimized for aligning images with text rather than preserving these detailed linguistic structures. As NLP developed, GloVe in 2014 improved word representations using global co-occurrence statistics. In 2018, BERT introduced a transformer-based approach, providing context-dependent word representations and setting new performance benchmarks. Following this, large language models (LLMs) like GPT-2 and GPT-3 emerged and further refined language understanding. While these models shifted focus toward richer contextual embeddings, the legacy of explicitly encoding relational properties gradually diminished, making modern VLMs like CLIP sensitive to linguistic variations.

We will start our story with an observation as following:

Semantic Disconnection: Uncovering CLIP’s Latent Space Limitations

One major issue is that CLIP’s latent space struggles to capture semantic differences in their pretraining stage. Consider these observations:

- Synonyms vs. Antonyms: The cosine similarity between synonyms can be even lower than that between obvious opposites. For example

- $\cos(\textit{happy}, \textit{sad}) = 0.8 \quad > \quad \cos(\textit{happy}, \textit{cheerful}) = 0.79$

- $\cos(\textit{smart}, \textit{dumb}) = 0.8 \quad > \quad \cos(\textit{smart}, \textit{intelligent}) = 0.75$ And, this is a common phenomenon for all words in the WordNet hierarchy!

- Template Variability: When words are embedded in different prompt templates, experiments reveal that only about 30% of expected semantic relationships remain consistent.

These challenges underscore why traditional methods—such as manual prompt engineering or static fine-tuning—often fall short. They are typically time-consuming, narrowly focused, and lack the ability to generalize across varied datasets or scenarios.

Methodology - Power of Wu-Palmer Similarity

Our approach focuses exclusively on fine-tuning the text encoder while leaving the image encoder unchanged. The key idea is to explicitly incorporating lexical relationships and adjust the text embedding space such that:

- Equivalent Expressions are mapped closer together.

- Other Words are pushed further apart.

Inspired by network embedding methods that are explicitly designed to preserve structure, we seek a metric that captures these inherent relationships. This motivation leads us to the Wu-Palmer Similarity, which is a measure used to quantify the semantic similarity between two concepts within a taxonomy, like WordNet. It relies on the depth of the concepts and their Least Common Subsumer (LCS), which is the most specific ancestor common to both concepts.

Wu-Palmer Similarity

The similarity between two concepts ( c_1 ) and ( c_2 ) is given by:

\[\text{sim}_{wup}(c_1, c_2) = 2 \times \frac{\text{depth}(LCS(c_1, c_2))}{\text{depth}(c_1) + \text{depth}(c_2)}\]where:

- $depth(c)$ denotes the depth of concept $c$ in the taxonomy.

- $LCS(c_1, c_2)$ is the least common subsumer of $c_1$ and $c_2$.

- Range: The similarity score ranges from 0 to 1, which is same as $cos$ function.

- Higher Score: A higher score indicates a greater degree of semantic similarity, as the concepts share a more specific (deeper) common ancestor.

Custom Loss Function

Our training objective is to fine-tune the text encoder using a composite loss that consists of two parts: a distance loss and regularization loss. Given two tokenized word vectors $w_i$ and $w_j$ generated by the model $M$, the losses are defined as follows:

1. Distance Loss

This component enforces that the cosine similarity between the embeddings $M(w_i)$ and $M(w_j)$ approaches a target similarity derived from the Wu-Palmer metric. Mathematically, it is given by:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{distance}}(w_i, w_j) = \left(c\times \Bigl( s_{\text{WP}}(w_i, w_j) - \cos\theta \bigl(M(w_i), M(w_j)\bigr) \Bigr) \right)^2\]where:

- $s_{\text{WP}}(w_i, w_j)$ is the Wu-Palmer similarity between $w_i$ and$w_j$ and $c$ is a constant.

- $\cos\theta \bigl(M(w_i), M(w_j)\bigr)$ is the cosine similarity between their embeddings, generated by $M$ in current state.

2. Regularization Loss

To prevent the fine-tuning process from deviating too far from the original embeddings, we introduce a regularization term. This is computed as the Euclidean Distance between the current embedding $M(w)$ and the precomputed original embedding $M_0(w)$ for each word $w$:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{reg}}(w) = \text{Euclidean}\Bigl( M(w), \, M_0(w) \Bigr)\]This term is scaled by a regularization strength multiplier $\lambda$

Overall Loss Function

The combined loss function that is minimized during training is:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{distance}} + \lambda \, \mathcal{L}_{\text{reg}}\]This loss encourages the model to adjust its embeddings so that:

- The cosine similarity between $M(w_i)$ and $M(w_j)$ closely matches the target Wu-Palmer similarity.

- The embeddings do not stray too far from their original values, by the regularization term.

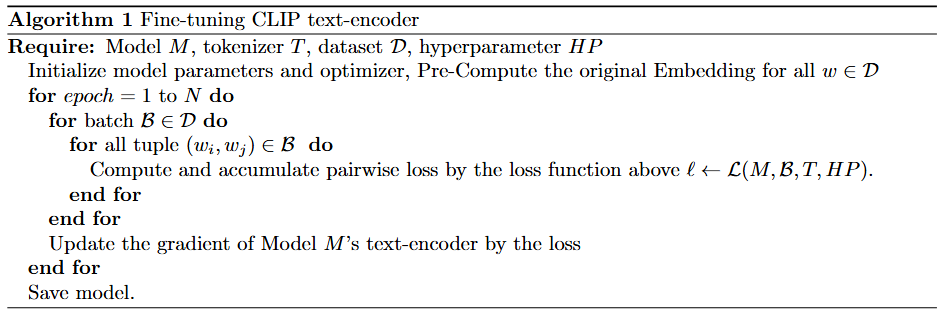

Training Loop

The training process involves iteratively updating the text encoder based on the computed loss over all word pairs. The high-level algorithm is as follows:

Benefit

By applying our method, we can

- Improve Adaptability: Enhance CLIP’s robustness when dealing with the inherent variability of natural language.

- Minimize Overhead: Achieve these improvements with minimal computational cost, all without requiring additional image content.

- Boost Accuracy: Preliminary results indicate that our approach can enhance the image classification accuracy noticeablely while using synonyms or hypernyms in classnames, as well as original classification accuracy, across multiple datasets

This innovative method take a step toward overcoming the linguistic rigidity of CLIP, potentially paving the way for more robust and versatile vision-language applications.

Stay tuned as we delve deeper into the experimental insights and future directions of this research.

Experiments

Datasets

- FER2013: The Facial Expression Recognition 2013 (FER2013) dataset have 7 classes. We select this as a showcase in small-scale experiment since their class names have rich synonyms.

- ImageNet: The ImageNet dataset is a large-scale image database designed to advance visual recognition research that organized according to the WordNet hierarchy. This is also the only large image-classification dataset which have official mapping to WordNet, which our method is currently relying on.

- OpenImage: The OpenImages dataset is similar to ImageNet. We carefully select 200 classes and assign WordNet Mapping to its class names with gpt-4o with human verifier.

Subset Creation

In this experiment, we focus exclusively on subsets of class labels for which synonyms or hypernyms are available in WordNet. To minimize potential disturbances, we ensure that all words within each subset are unique during the subset creation process.

For the hypernym setting, we limit our use to direct (level-1) hypernyms in the WordNet hierarchy, as higher-level hypernyms tend to be overly abstract and less applicable in practical real-world scenarios.

Evaluation Strategy

To evaluate the effectiveness of our method, we compare the zero-shot classification accuracy with the original pre-trained model1 and our fine-tuned version on two sets of class labels: the original class names and the class names replaced by their corresponding synonyms or hypernyms. We select distinct subset and combination to reduce variations

Results

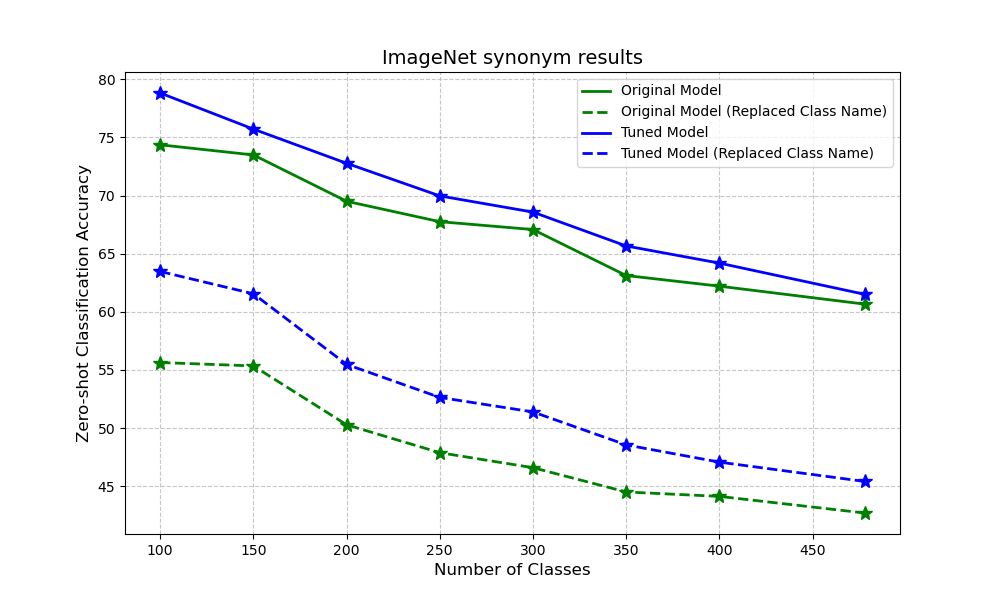

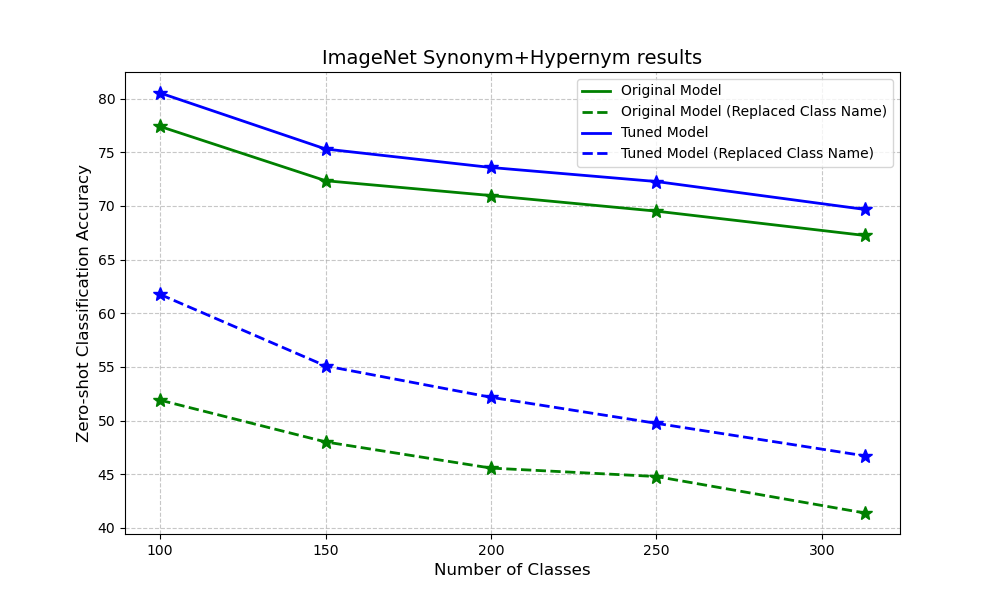

Our method improves classification performance in both synonym setting and hypernym setting across different datasets. In ImageNet, we also conduct experiment on Mixing synonyms and hypernyms

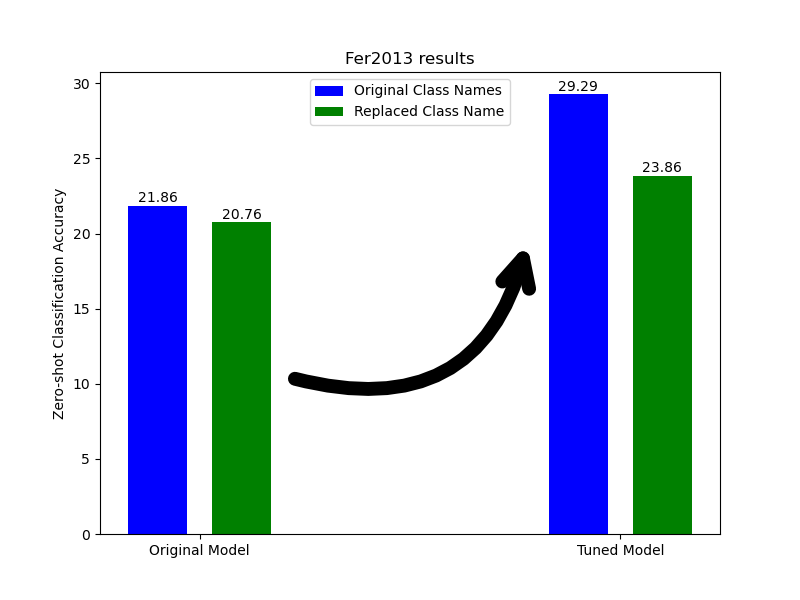

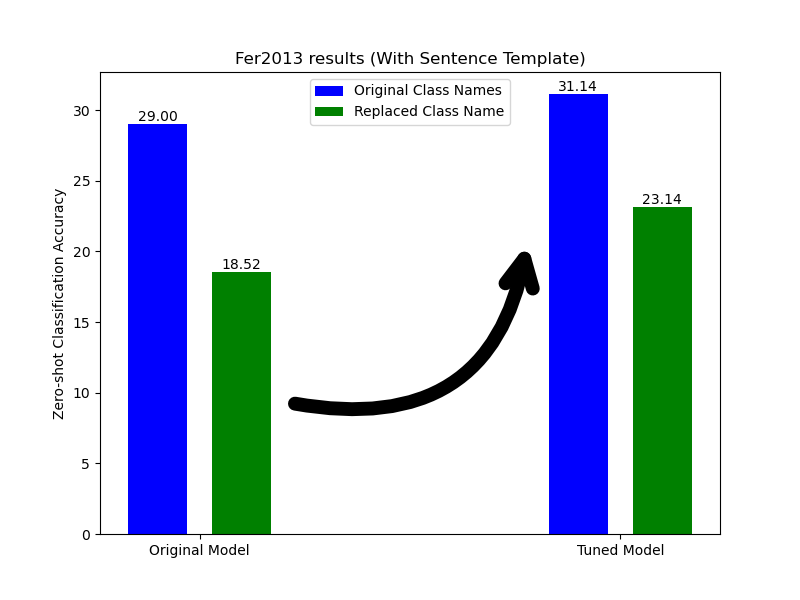

Fer2013

As a starting point, we test our method’s capability on Fer2013 dataset. The tuned model demonstrates a notable increase in accuracy for both the original class labels and those replaced by synonyms whenever we use sentence template in the classification

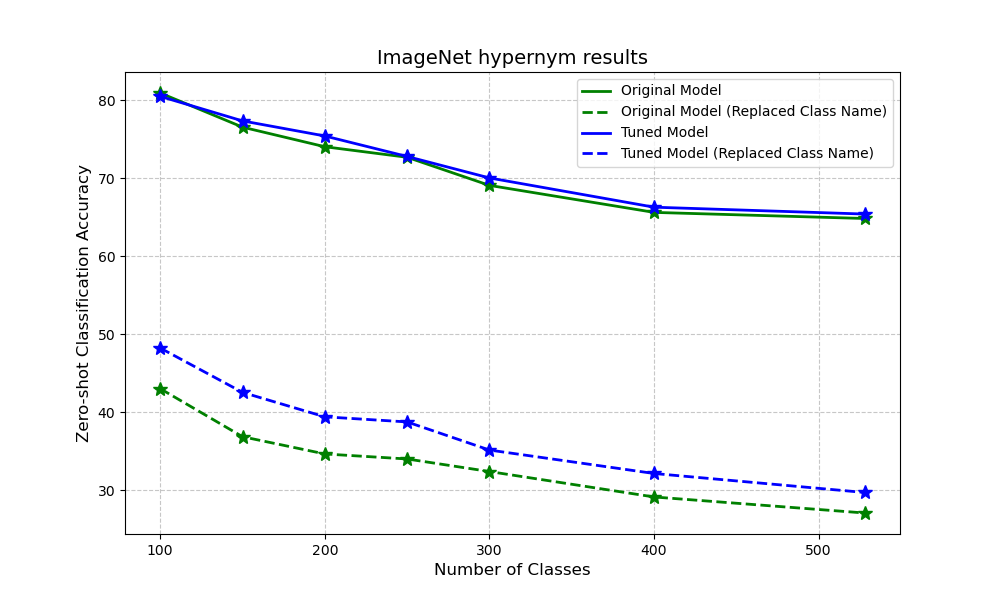

ImageNet

Our ImageNet experiments show that fine-tuning not only boosts accuracy when we swap label names with synonyms or hypernyms, but it also improves zero-shot performance using the default labels. This means our method helps the base model get a better handle on semantics and generalize more effectively.

We conduct our experiment in all of three setting below.

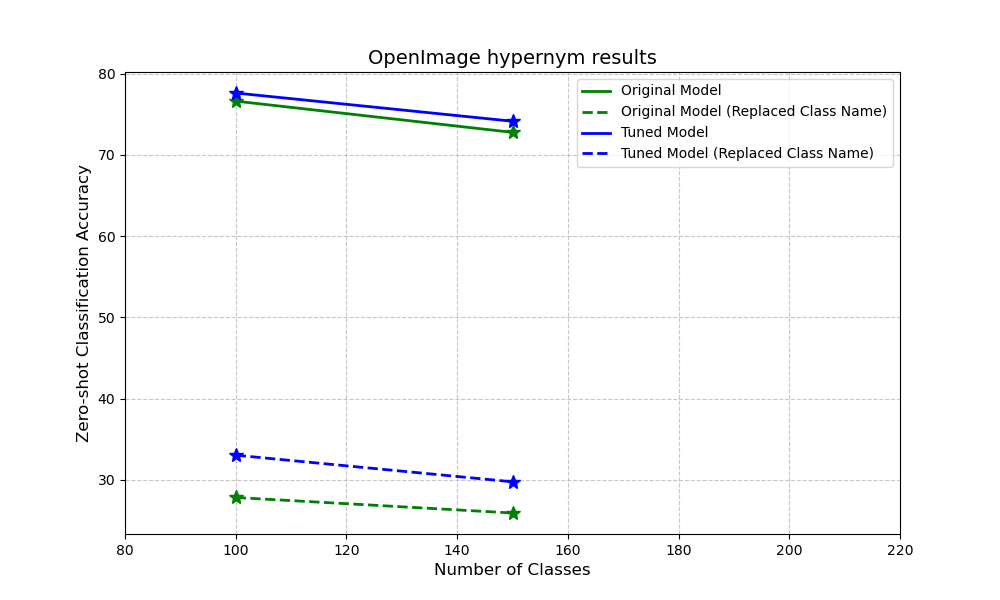

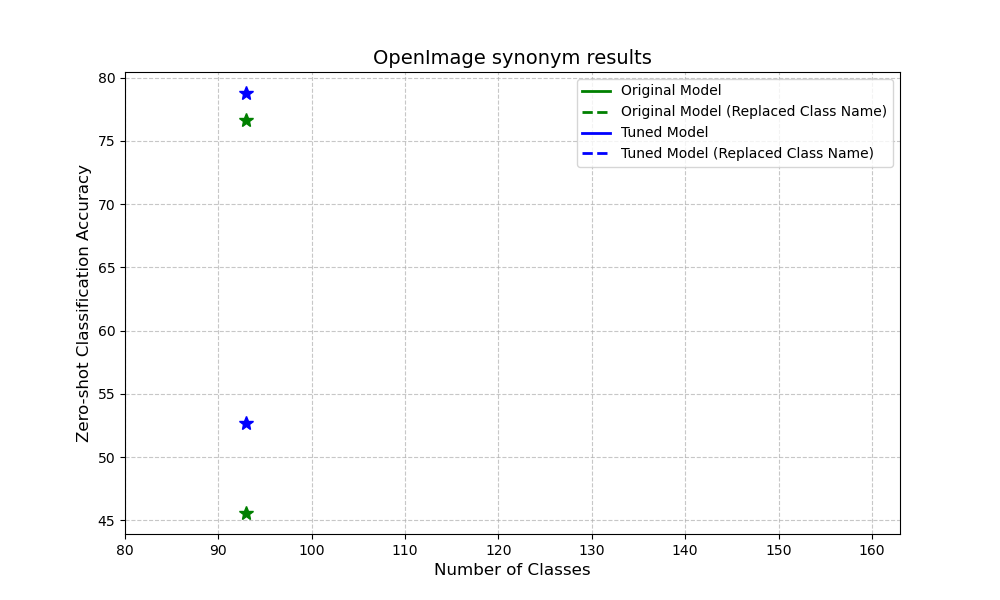

OpenImage

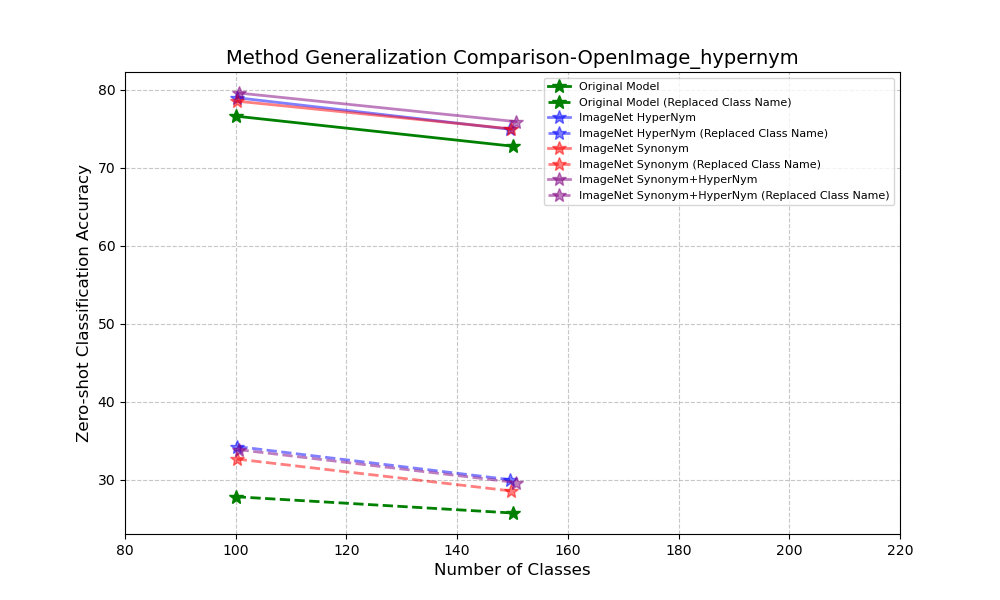

To show adaptability of our approach, we also craft a subset of OpenImage to conduct similar experiment as we did imagenet. We observe a similar pattern of improvement

Generalization

Now, let’s see how well our method generalizes. We’ll show that a model fine-tuned on different ImageNet subsets can also boost the classification accuracy on the OpenImage subset.

Discussions & Conclusions

In this post, We explored a simple way to fine-tune CLIP’s text encoder without heavy computation—by aligning synonyms and hypernyms in the text embedding space. This tweak improves zero-shot classification accuracy across various datasets without even needing image content. Looking ahead, we’ll refine this approach and test its real-world applications to better connect language and vision.

Takeaways and Future Work

Our exploration of fine-tuning CLIP’s text encoder has revealed several critical challenges and exciting directions for future research:

Scalability/Polysemy Challenges:

In WordNet, 31989 out of 148730 words have polysemy. This inherent ambiguity could compromise the integrity of the underlying data structure as we scale up, necessitating advanced techniques to manage multiple word meanings effectively. In the experiment part, we also observe a decreasing marginal gain on our proposed method when we increase the number of classes. While 53811 out of 117659 words have synonym in wordnet, scaling is another concern. Both of which underscoring the need for scalable and robust solutions.Adapting to Image-Caption Datasets:

For broader applicability, we need to adjust the current methodology to work with image-caption datasets like LAION and Conceptual Captions. This adaptation could pave the way for more versatile and comprehensive vision-language models.Limitations with Propositional Words:

Frameworks like CLIP struggle with propositional terms such as not, is a, or comparative expressions like more/less than. These limitations hinder the model’s ability to fully grasp complex semantic relationships.

We hope you enjoyed our post! Our code is also released in Github.