AutoWS-Bench-101: Benchmarking Automated Weak Supervision on Diverse Tasks

Published:

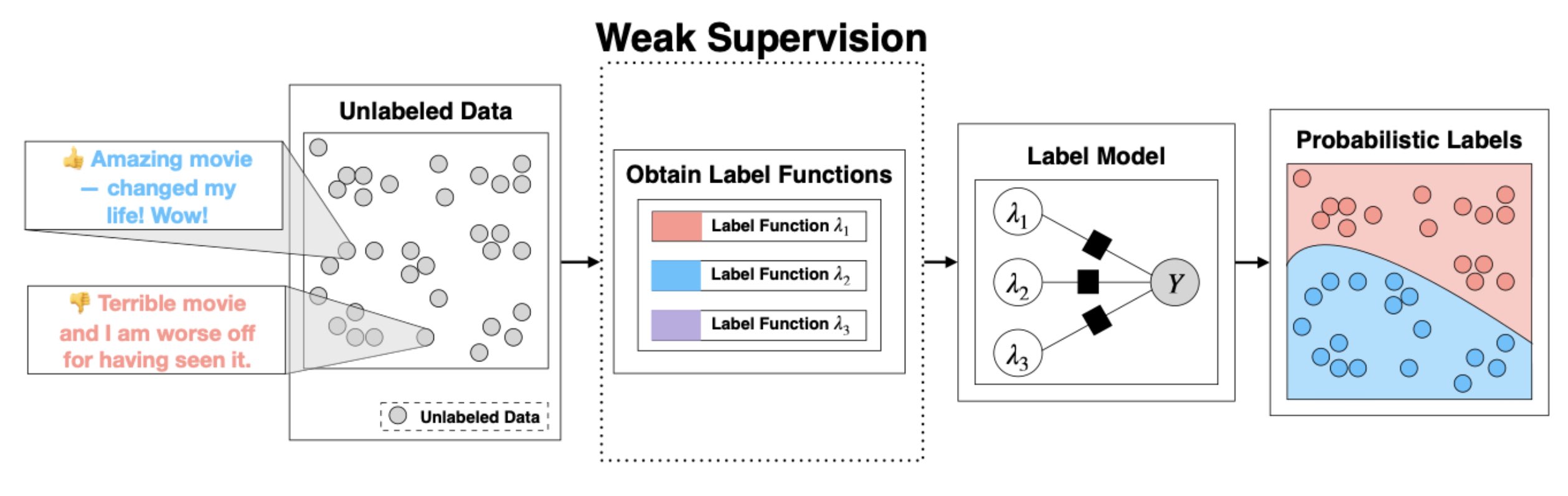

It’s no secret that large-scale supervised machine learning is expensive and that one of the biggest challenges is in obtaining the labeled data required for training machine learning models. Weak Supervision (WS) a popular and quite successful technique for reducing this need for labeled data. WS relies on access to noisy, heuristic functions that produce reasonable label guesses–these are called labeling functions, or LFs for short. Given a handful of these LFs, WS attempts to learn the relationships between the LFs and the true but unobserved label–the component that does this is called the Label Model. WS is fairly easy to apply to text data, it’s harder to apply to data with more complex features. Automated Weak Supervision (AutoWS) solves this problem by instead learning the LFs using a small amount of labeled data. The beauty of all of this is that WS and AutoWS can be combined with other ways of dealing with a lack of labeled data, like zero-shot learning with foundation models, or self-supervised learning. In this blog post, we will shed some light on AutoWS and explain the motivation behind our AutoWS-Bench-101 benchmark, the first-ever benchmark for AutoWS!

Weak Supervision by example: Rotten Tomatoes

Let’s step through a quick example of WS on movie review data… Here, the goal is to classify Rotten Tomatoes reviews as either “Fresh (+)” or “Rotten (-)” Suppose we start off with three LFs, and for simplicity, we will use majority voting as our Label Model:

- LF1 returns “Fresh” if the movie review contains the word “amazing,” otherwise don’t vote,

- LF2 returns “Rotten” if the movie review contains the word “nightmare,” otherwise don’t vote, and

- LF3 returns “Fresh” or “Rotten” depending on the prediction of an off-the-shelf sentiment classifier.

Now let’s apply these LFs to the following review of the 2019 movie Cats:

"At best, it’s an ambitious misfire. At worst, it’s straight-up nightmare fuel that will haunt generations. Enter into the world of the Jellicles at your own peril."

Most people would probably assign this review the label “Rotten,” though since we’re doing WS, let’s check to see if our LFs agree… LF1 doesn’t vote because the word “amazing” does not appear in the text, LF2 votes “Rotten,” and for the sake of argument, suppose that LF3 also votes “Rotten.” Since we’re aggregating these LF outputs using majority vote, WS correctly labels this review as “Rotten.”

The purpose of this example was twofold: first, if you aren’t familiar with WS, this example was hopefully illuminating. And second, that it’s easy to write LFs for text data! The “features” that come with text (i.e., words) are more intuitive for humans to reason about, which makes it easier to come up with fairly general rules for text tasks.

But what about data with more complex features, such as images? To our knowledge, traditional WS hasn’t even been applied to MNIST, because writing LFs from scratch for raw pixel data is simply not practical.

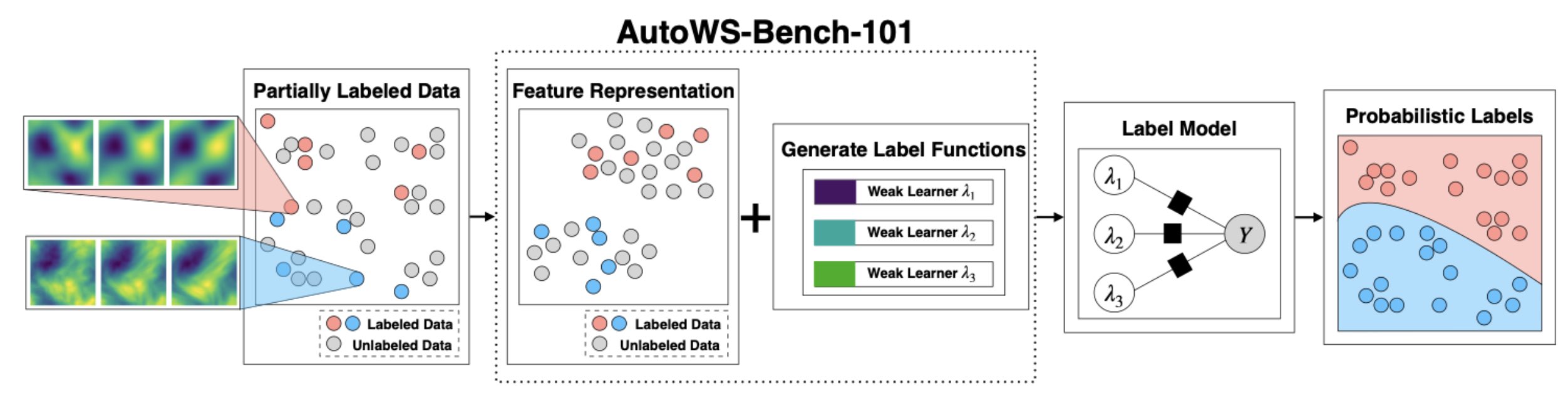

From WS to AutoWS

Fortunately, dealing with more complex features only requires a few extra steps… The general idea is to learn the LFs using a small set of labeled examples instead of writing the LFs by hand. This technique is called Automated Weak Supervision, or AutoWS, and the pipeline illustrating this process is shown in the above diagram. What makes traditional weak supervision difficult for things like images is that they are typically represented as tensors of pixel values, and it is challenging for a human to write explicit LFs on the pixel level to classify these data. Of course, this is true of other data types as well–including things like PDEs, which are often used for physics simulations, medical data, and featurized tabular data.

The first step in most AutoWS techniques is to obtain a more useful representation of the complex data. This is typically done by using some form of dimensionality reduction, by either using a classical technique such as PCA or by using an embedding obtained from a modern foundation model.

Next, AutoWS techniques often use some small set of existing labeled examples to train simple models in this feature representation–these are called weak learners, and these will be used in place of the hand-designed LFs used in traditional WS.

Finally, we proceed with the rest of the original WS pipeline by learning the parameters of the LM and we generate training data! Except now, we can generate training data for much more complex and diverse domains, including a large variety of previously challenging scientific domains.

Armed with the two key takeaways from our deep dive into AutoWS methods,

- AutoWS methods mostly comprise two steps: feature representation, and obtaining weak learners

- AutoWS methods unlock a huge variety of diverse applications for WS we developed our first-ever benchmark for AutoWS methods: AutoWS-Bench-101.

AutoWS-Bench-101

With AutoWS-Bench-101, we benchmark AutoWS methods using only 100 initial labeled examples, which gives our benchmark its name, as our goal is to generate the 101st label onward! We do so by applying the two previously-mentioned takeaways–we evaluate the cross product of a set of feature representation methods with a set of AutoWS methods, and we do so on a diverse set of applications.

In particular, we tried a wide range of feature representation techniques, of varying complexity–simply using raw features, PCA, an ImageNet-trained ResNet-18, and features from CLIP–a modern foundation model. We plug each of these into a handful of AutoWS techniques, including Snuba, Interactive Weak Supervision, and GOGGLES.

Our benchmark comprises three main categories of datases:

- Image tasks

- NLP tasks

- diverse tasks

In the first category, we include MNIST, CIFAR-10, a spherically-projected version of MNIST, and MNIST with permuted pixels. Next, for backward compatibility with WRENCH, a benchmark for WS, we include three of the NLP datasets from their benchmark: YouTube, Yelp, and IMDb. Finally, we include three datasets from diverse application domains, where we think that AutoWS is quite promising: electrocardiograms (ECG), classifying the turbulence of a PDE (Navier-Stokes), and malware detection (EMBER).

Key takeaways from AutoWS-Bench-101

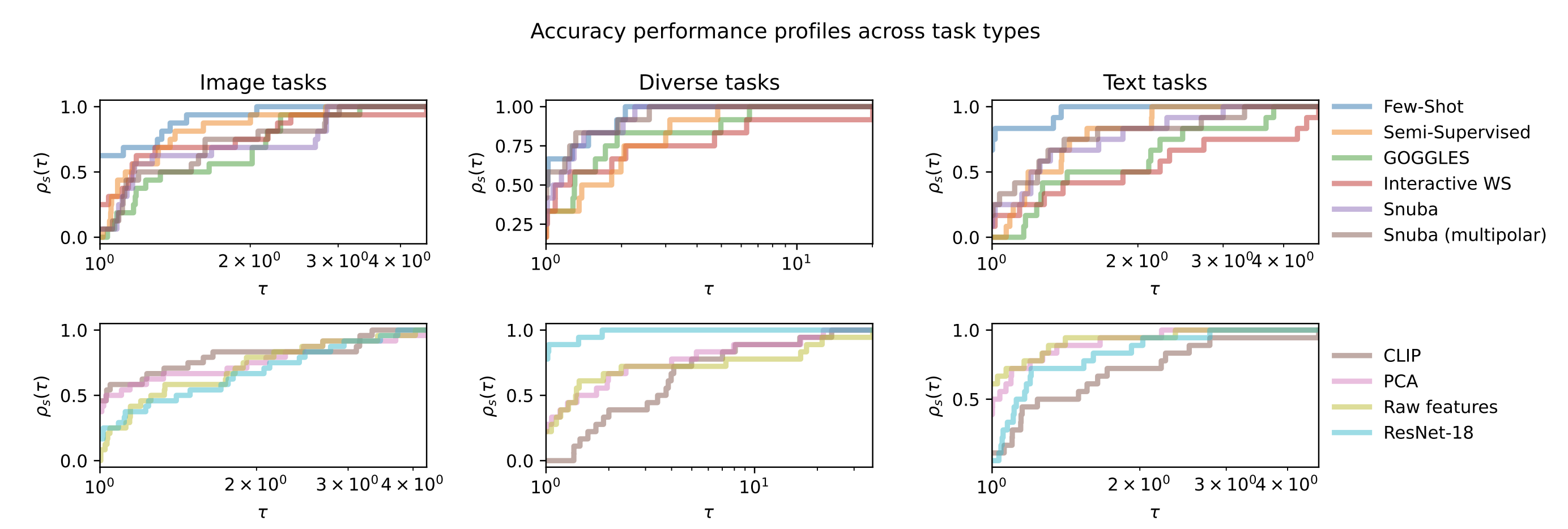

The standard of evaluation for AutoWS-Bench-101 relies on performance profile curves, which are a holistic way to evaluate different methods across various settings or “environments.” We won’t go into too many details of how these are computed here, and instead, I’ll refer you to a nice blog post by Ben Recht on the topic. The key idea of performance profiles is that the higher curves are better for most tasks, or at least close to the best method for a given task, and the curves themselves are able to express situations in which a method is actually dramatically worse than the best method.

The standard of evaluation for AutoWS-Bench-101 relies on performance profile curves, which are a holistic way to evaluate different methods across various settings or “environments.” We won’t go into too many details of how these are computed here, and instead, I’ll refer you to a nice blog post by Ben Recht on the topic. The key idea of performance profiles is that the higher curves are better for most tasks, or at least close to the best method for a given task, and the curves themselves are able to express situations in which a method is actually dramatically worse than the best method.

Using performance profiles, we were able to see several interesting trends across our three categories of datases:

- few shot learning actually does better on vision and NLP tasks than many AutoWS methods, however, on diverse tasks, AutoWS catches up,

- CLIP is very useful for vision tasks, but not for diverse or NLP tasks, in part due to a lack of compatibility,

- an ImageNet-trained ResNet-18 model is surprisingly helpful for diverse tasks, despite being far afield from ImageNet.

Using our benchmark, we also came away with these other key findings:

- Foundation models are only helpful to AutoWS for in-distribution or related tasks,

- LFs that output multiple classes might be better than class-specialized LFs,

- Foundation model usage can hurt coverage, the fraction of points labeled by AutoWS.

For more details about these findings, and our ablation studies of the various AutoWS methods that we tried, check out our paper! 😃

And if you arrived at this page by scanning our QR code at NeurIPS, and you made it all the way here, here’s a cookie. 🍪

What’s next for WS and AutoWS benchmarking? Concluding thoughts and ideas…

We’re excited to add more functionality and methods to AutoWS-Bench-101! But beyond this benchmark and WRENCH, what is left to do? I mentioned before that WS and AutoWS can be combined with zero-shot learning with foundation models and self-supervised learning… But how do we find out which methods, or combination of methods, are actually the most useful for different types of tasks?

I am personally excited about the idea leveraging community involvement to answer these big questions. As an organizer of the AutoML Decathlon competition at NeurIPS 2022, one idea that I’m excited about is to run a Weak Supervision coopetition–a cooperative competition. The idea behind this is to solcit LFs for a set of diverse tasks with mostly unobserved labeles from the community–and cooperatively solve the challenge of programmatically-labeleing large datasets via a Kaggle-like interface. I like this idea because it is goal-driven: the community must find a way to label these datasets by any means necessary, and everyone can help one another out by contributing to a shared GitHub repository. I think that this could be similar to something like Google Big-Bench, with the promise of publishing a paper with many authors, and the eternal glory of having contributed to a large-scale (possibly registered + peer-reviewed) supervision experiment.

Whether the next steps for WS benchmarking end up being related to this idea of a coopetition or something entirely different, I’m super excited to see where we go next with reducing the need for labeled data!

Nicholas Roberts nick11roberts@cs.wisc.edu